|

|

#1

|

|||

|

|||

|

Katy PMed me and asked me to start a Lounge thread on the economy, specifically addressing things like:

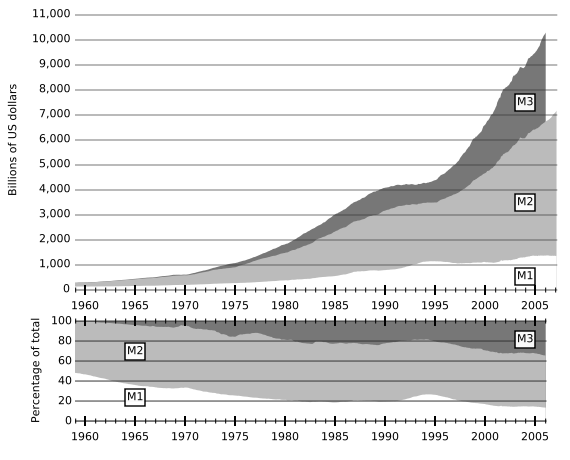

[ QUOTE ] . . . what's happening to our economy and what we can expect in the near future. For example, why is it bad for the feds to cut the interest rate? What is the meaning of "sub-prime" lenders and how is it that a few people defaulting on their loans could push the entire world into an economic crisis? [/ QUOTE ] While I am taking a stab at this, opinions are greatly varied and other people on the site disagree with my interpretations. They are certainly welcome to post their views as well. And I welcome all questions. Let's just please, please, please try to keep it Lounge-worthy, i.e. civil. I hate to have to ask this, but very often I've found that people with differing views on such things often cannot restrain themselves from hurling insults (myself included [img]/images/graemlins/tongue.gif[/img] ). Ok! Here's a little background, X-posted from a BFI post I just made, on how the Fed lowers interest rates by expanding the money supply, and what the negative effects of this are. It was in response to a question about some people (who generally subscribe to what's called the Austrian School of economics, like me) that claim that the Fed "prints money out of nothing": [ QUOTE ] When we say "printing money form nothing", it's a figure of speech. The money doesn't need to be physically printed to expand the money supply. An entry is simply created in an electronic account at the Fed, and then the Fed purchases government securities from special brokers during "Fed Time" in open market operations with that newly created money, via wire transfer I believe (although I'm not sure; the Fed might physically cut a check). Those brokers then deposit those funds in the commercial banks, where they become increased reserves for the banks. If commercial bank reserves are increased by $50B in this manner, the banks can then create up to a total of $500B via loans, by the magic of fractional reserve banking, if the reserve rate is 10% for example. The artificial lowering of the interest rate of course encourages people to take out these loans, which is what actually does most of the expansion of the money supply. <font color="white"> . </font> The important number is not the total of physical cash, but the total of fiduciary instruments, M3: <font color="white"> . </font>  <font color="white"> . </font> Before the Fed stopped reporting M3 (supposedly because it "cost too much" to measure; this from the people who can create money), M3 was expanding at about 15% per year. <font color="white"> . </font> And once again I will point out that artificially lowering the interest rate, which is really the market price for investment funds and hence access to physical resources, causes a misallocation of those physical resources, just as any price cap on any good or service causes a misallocation of that good or service. If you cap the price of milk at $0.25/gallon, people would be bathing in milk and watering their lawns with it, and a shortage would develop. That's what happens to the physical capital stock when the interest rate is artificially capped; productive capacity is misallocated and a shortage develops that is eventually revealed in, and correct by, a recession. [/ QUOTE ] Now, as for why the Fed does this, the going explanation is that without careful management of the money supply, the market economy is inherently subject to periodic instability, called business cycles, which are alternating "booms" and "busts". The claim is that a central bank must manage the money supply to navigate the economy through these, cooling off the booms and heating the economy back up in the busts. The Austrians would claim that it is bank credit inflation and the associated artificial lowering of the interest rate that causes the business cycle, of artificial booms and the busts required to correct them, in the first place. Austrians don't think that those within the Fed are stupid, however. After all, Alan Greenspan was an Austrian for decades before he took the reigns of the money supply. We are very cynical about why an institution like the Fed would want a monopoly of the power to legally create money out of nothing, and very cynical about the reasons for and timing of the artificially created booms. It is much easier to be re-elected for a second term as president if the Fed has turned on the money spigot, generating an artificial boom after the recession caused by your predecessor's re-election boom, and by the time your second term is up and your recession hits, it's the next administration's problem. If you look at the one sustained period of almost zero increase in the money supply in the graph above, it is the reign of George H. W. Bush, who still bitterly complains that Alan Greenspan cost him re-election. For a more extensive overview of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT) see this post. On to the next question, which was about "sub-prime" lending. This is part and parcel of another general problem with credit expansion: asset bubbles. Expansion of the money supply eventually drives up prices, creating price inflation (the pattern and time structure of this inflation is complex, and I won't go into it; suffice it to say that not all prices go up equally or at the same time, and in fact some prices don't go up at all; they will fall). Investment funds, seeking to stay ahead of inflation, will tend to find their way into certain asset classes, which could be anything, stocks, real estate, art, etc. and create asset bubbles, or sectors of the economy that are particularly overvalued. The entire economy is actually bubbled because the lowered interest rate tends to trick entrepreneurs into making mistakes all across the economy, but some areas are always more bubbled than others. In any event, one of the latest bubbled sectors of the economy is housing, which the Austrians and others were pointing out as early as 2002 and 2003. The last big bubble we all heard about was the "dot com" bubble, i.e. technology stocks. So what is sub-prime lending? Well, when there is a market clearing interest rate, that means that everyone that wants to borrow at the market rate and everyone that wants to invest at the market clearing rate can always find someone to do business with. By lowering the interest rate, you trick buyers into entering the market who would not have entered the market at the real rate. "Sub-prime" lending basically refers to creating loans for buyers who would not have been able to get loans before, either because of credit problems, income, or whatever. Obviously the risk of default on these loans is higher than normal. The reason that this happened (and none of the people involved was stupid) was the asset bubble in real estate values. People saw real estate values rising so fast that buyers would be gaining equity so fast that the riskier loans appeared to be justified. The problem is that all bubbles must eventually burst. When the housing bubble started to burst, and real estate values began to fall, suddenly a lot of people are revealed to be WAY upside down in their mortgages. Now, even though foreclosures are up something like 400%, that's not the real issue. That is still a tiny fraction of homeowners being foreclosed on. The real problem is what was done with all of these mortgages. They were packed up and sold as securities, so-called Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS's). Now the MBS's became a VERY popular investment vehicle when the real estate market was hot. And there was then a secondary asset bubble in MBS's. A LOT of big financial institutions, foreign and domestic, invested a lot of money (hundreds of billions of dollars) into these securities. And now that the real estate bubble has popped, the underlying market value of these securities has also popped, and the banks have had to "write down" billions and billions in losses on these instruments. Accompanying all of this is the "credit crunch". People generally think the credit crunch is being driven by the sub-prime crisis, but it is more fundamental than that. The credit crunch is not tied to one sector, its economy wide, and it is a result of the earlier credit expansion. When the interest rate is lowered, it causes entrepreneurs all over the economy to believe that all sorts of new projects are profitable. Let's say the real interest rate is 8%. A project that returns 7% would be unprofitable to take out a loan with which to undertake it. But if the interest rate is artificially lowerd to 5%, that project looks profitable, and a business might take out that loan and start that project. The problem is that as entrepreneurs all over the economy are doing this, they start bidding up the prices of the inputs, the physical factors of production like steel, energy, computers, machines, equipment, labor, office and warehouse space, etc. There aren't enough physical factors of production to complete all these projects, and they eventually bid up the prices of the inputs to the point where the project is revealed to be unprofitable. The rising input prices cause an increase in the demand for loanable funds, which tries to drive up the interest rate, the "credit crunch". The Fed can either maintain the low interest rate by injecting more "liquidity", i.e. money, which it cannot do indefinitely, or it can let the interest rate rise, revealing all of these projects throughout the economy to be unprofitable malinvestments, which kicks off the recession. It is really not that the sup-prime mortgage crisis will "spill over" into the rest of the economy. The rest of the economy is also bubbled. It's just that one sector happened to be the first to pop, real estate. That dominoed into the MBS asset bubble. That dominoed into the financial institutions. Technology stocks are showing weakness, and I even saw that the art market took a massive hit. In 2000 it was dot coms and tech stocks that were the first to go, but they didn't drag the rest of the economy down with them; the rest of the economy was already poised to go. When 9/11 crashed the stock market, it didn't really do a trillion dollars of economic damage as I've heard people claim. That trillion dollars in economic damage had already been done by monetary inflation. It was just that the recession of 2000 and the acceleration of 9/11 revealed it. We have that same scale of economic damage now driven by the last 6 years of monetary inflation; it's just that it hasn't yet been fully revealed, and it probably won't be revealed quite so quickly. Lastly, I will talk about the dollar. For many years now the Fed has been expanding the money supply at a rapid pace. We have not seen very much of this in consumer prices for a couple of reasons. One, a large fraction of those new dollars go out of the country and end up being held by foreign central banks, mostly asian and middle eastern, as their reserves, on top of which they print their own fiat currencies. China alone holds something like US$1.5T. We have basically been exporting inflated dollars and importing real goods and services. This drives our massive trade deficit, and allows us to literally exploit the world (we get goods and services, they get green pieces of paper or electronic entries representing them). Another part of the monetary expansion is hidden in increasing productivity. If the money supply expands at 5% but productivity also rises at 5%, then prices will appear to be stable, even though monetary expansion and malinvestment is still occuring (this was the case in the 1920s). Now the problem is that by expanding the money supply, you obviously increase the supply of dollars. Since all the other countries are also expanding their money supplies, if the US expanded at the same rate as everyone else, there wouldn't be any general long term weakening in the dollar vs. other currencies like the Euro. But this isn't the case. The Fed has inflated the dollar supply at a faster rate than other currencies are being inflated, which lowers its international purchasing power relative to those currencies, weakening it relative to them. As the value of dollar holdings falls, people seek to get out of dollars, either by selling them on currency markets, which further increases their supply and lowers their demand, further lowering their value, or by buying up assets for US dollars, which drives up asset prices. As the value of the dollar falls internationally, the best place to buy assets like real estate and companies for US dollars will be the US. So foreign investment will go up, our exports are going up, but all those inflated dollars coming home to roost will drive up domestic prices. So what we are set for is staglation; we are entering a recession at the same time we will see significant price inflation. The last time this happened was the 1970s, and that occured for largely the same reasons it is happening now. This turned out to be a much longer post than I thought. Keep in mind that others will greatly disagree with my interpretation, and I don't claim that my understanding of abstruse investment instruments like mortgage backed securities is perfect. I welcome thoughts, corrections, questions, and other contributions. |

|

|